Choir & Organ

|

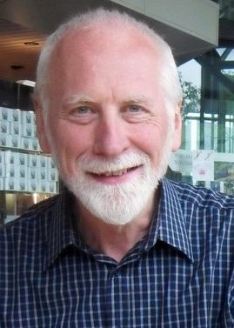

Choir & Organ [May/June 2002] In conversation with Christopher Herrick who turned 60 this* month, Malcolm Bruno discovers a maverick who has never been afraid to take risks... The Right Man 'Well... I suppose it might be just possible to be an organist giving concerts, with no permanent church appointment - but even Thalben-Ball has a city church.' These were the sceptical, if amiable, words of Sir John Dykes Bower, then organist of St Paul's Cathedral, London, to his young protégé, Christopher Herrick in the mid-1950s. Herrick, in his early teens, had been a chorister at St Paul's and in his last year had assisted Dykes Bower at the keyboard. 'It was that experience, like a religious conversion, that convinced me that I had to devote my life to mastering such an incredible instrument. Until then I had been a lazy young pianist, but the taste of 'being in the cockpit' was a transformation for a 13-year-old boy, especially at St Paul's.' 'There were some amazing events. Not only the normal services, but even a coronation in 1953. And later that year a three-month tour of America. In those days, of course, it wasn't a quick flight, but crossing on the Queen Elizabeth and then ten weeks of Greyhound buses zig-zagging across the eastern USA and Canada. We didn't get much work done academically, but America itself, after post-war England, was an education. A packed Carnegie Hall in New York, breaking all local box office records, was thrilling, but so was a private concert in the White House and a meeting with President Eisenhower.' As the thrill of Fifties America comes into his voice, one can see how the stage was set in his early years for the energy required of a touring virtuoso. Oxford Herrick's 'madness' for the keyboard continued throughout his school days, and his vigilance landed him an organ scholarship at Exeter College, Oxford. 'There was no performance element at all in the music degree in those days, so I had to learn on the hoof. During term I did as much playing and practice as I could, as well as coping with men's and boys' services - which I did instinctively. But in the breaks, I crammed in all the academic work. 'I remember being completely taken by Monteverdi, who was then to most performers a non-existent composer. The more I studied his music, the more it seemed so incredible. And during 1959-60 Sir Jack Westrup was giving a series of lectures about Monteverdi's operas. At each lecture the numbers of the initial 50-strong audience dropped exponentially until it was just the two of us. But his style remained as formal as for a room full of students. And I remember asking him at the end of the series, "do you think these wonderful operas will ever be performed again, by opera companies?" to which his reply was "oh no, certainly not!"' Royal College of Music By the conclusion of his Oxford degree, Christopher was certain that he needed practical musical training, so he enrolled with a Boult scholarship at the Royal College of Music in London. 'The harpsichord had also fascinated me, and Millicent Silver (a total Landowska devotee if ever there was one) became my professor. From a historical point of view, of course, everything about her approach was wrong. And so was the instrument, a massive Goble complete with a crescendo pedal. But the experience of working with her gave me a vivid taste of an unknown world. And she was such a fine, instinctive musician.' It was at this stage that Herrick approached Geraint Jones for private organ lessons. 'Like Millicent, he really cared and he could play!' It was very exciting to be his student at the time he was discovering the German mechanical instruments with their straight pedal boards, which forced him to develop a technique and phrasing that departed from the endless legato of Dupré's Romantic world. 'Conducting also came into my study at the RCM. While at Oxford I had found myself halfway through a Brahms Requiem with choir and orchestra and it dawned on me that I hadn't ever been taught any stick technique! In the intimate world of Anglican musicianship, directing emerges organically - imperceptibly - especially for a keyboard player.' And so Herrick's three years at the RCM included conducting study with Sir Adrian Boult as well. St Paul's Cathedral & Westminster Abbey After leaving the College, Christopher found himself to have Malcolm Russell, one of London's principal suppliers of harpsichords, as a neighbour. 'And quite effortlessly I acquired a Dulcken on permanent loan. It sat in my sitting room next to my Blüthner, which led quite effortlessly to the Taskin trio (violin, gamba, harpsichord). In the mid-Sixties, Seventies and even into the Eighties, baroque music on period instruments was pioneering music, which suited my temperament perfectly. But an opening at St Paul's as assistant organist did as well, to complement my early music activities.' Herrick's effortless musical pedigree seems equally matched to his high musical metabolism, for St Paul's led straight on to a decade (1974-84) as an organist at Westminster Abbey. 'Beyond all the routine services, I've counted that I gave some 200 solo recitals at the Abbey alone in that period!' And looking back he remembers great musical events, such as the funerals of William Walton and Herbert Howells, as well as the celebration of Walton's 80th birthday when all the composer's sacred music was performed, though he remembers Lord Mountbatten's funeral as the most moving event of his tenure. Hyperion Records The longer Herrick speaks, not only are his enviable energy and staggering achievement striking, but his 'maverick' propensity to take risks, deliberately to be the right man in the right place at the right time. In 1984 as he was about to leave the Abbey, one of these calculated 'non-accidents' happened. Christopher met Ted Perry, now better known as the owner-director of Hyperion (though in those days, his little-known three-year-old label seemed a last resort for many artists). The idea of organ music was totally unappealing, as was the name Christopher Herrick. But 'Westminster Abbey' was a different matter. Herrick shrewdly proposed an album of virtuosic repertory, taking the Abbey's Harrison & Harrison to its limits, and called Fireworks. Perry agreed cautiously. It was a success and slowly further recordings followed. 'He asked for Bach this time, but sternly warned me absolutely not to think of a series of complete works. Just the Trio Sonatas, perhaps.' From this humble beginning has come the most amazing sequence of recordings with 30 CDs for Hyperion to date: the organ Fireworks have now reached their ninth album and taken Herrick as far as Wellington, and the new Rieger in Hong Kong, to Reykjavik, Turku, St Bart's in New York and Berner Münster! And to complement the display of his instrument's immensity and power, has come a further series of organ Dreams with a third CD just completed. Like its extrovert sibling, organ Dreams are also eclectic. And then there are other one-off projects, like a CD of Daquin Noëls, or the album including Rheinberger's Suite for Organ, Violin and Cello. BBC 'Perhaps the most memorable of several recordings I made for the BBC was of Liszt and Mendelssohn organ works on the historic 1855 Ladegast organ in Merseberg Cathedral. It was in the Eighties before the end of Communism in East Germany. The church, after much arrangement, was offered, but even to get the organ tuned was a huge event. And it was cold. I remember that an ancient stove was placed between the organ bench and the Rückpositiv. But it was fantastic to record Liszt on this instrument. 'In fact, my life has been dedicated to playing this curious keyboard giant, of which no two are the same. And no two acoustics are the same. As a regular concert organist, you must accept that your life will not be like a pianist touring with or ordering the Steinway of your choice. If you can't cope with being versatile, you miss what the organ is about: in its physical nature (in the buildings and design), in its construction (from trackers to electro-pneumatics and back again), in its repertory. I love the challenge of making the most of the instrument and its ethos and all the music for it.' Complete Bach in New York Given the amazing list of Herrick's recitals and recordings, growing without pause from the mid-1980s, it's hard to imagine that anything but more of the same could top this. But there are always surprises. 'Well past midnight in early January 1998 my wife heard the fax machine go in my study downstairs. She went to retrieve it and said "stop relaxing!" And I certainly didn't get any sleep that night. It was my American agent offering an invitation from the Lincoln Center Festival in New York to play Bach - the complete organ works over the course of a 14-day festival. It was a dizzying thought, just to find the stamina to do it physically. But how could I refuse?' The collected Beethoven sonatas represent a feat of performance, but the complete Bach organ works, some 16 hours of music, top Beethoven's output for piano. It is neither just the length, nor the matter of big fugue after big fugue, two hands and two feet. There is registration: the Kuhn in New York's Alice Tully Hall was not capable of storing registrations. 'Looking back', Herrick reflects, 'I should have cancelled more activities in the period immediately preceding. The preparation was huge. I remember waking up one night about 3 am. I knew I wouldn't be able to get back to sleep, my brain was already practising. So I got up and went down to Kingston Parish Church, which is near my home, and was at its Frobenius just after 4.' The reviews of the series were exceptional, even more so coming from that bastion of early and sacred music scepticism The New York Times: 'Mr Herrick was at the peak of his considerable form, combining precision with panache, interpretive freedom with sheer joy in virtuosity. The playing was, in a word, triumphant.' Back at home Ted Perry at Hyperion celebrated with the promise of a box set (that complete-organ-works set that he had assured Herrick he never wanted to record), which comes out this year. Sweelinck And from here? A pick of recitals from churches throughout Europe and America flow in. Beyond his well-established Fireworks and Dreams series, what will be next on disc? Another commission has come through from Ted Perry: '"What", he asked me "about the complete works of Sweelinck?" I answered, "what about the best?", which is what we'll have, two and a half hours of selected music, spread over two CDs played on a faithful copy of the 17th-century organ of Stockholm's German church, which is now in Norrfjärden in northern Sweden.' Conducting Besides his insatiable affair with the keyboard, Herrick still finds time for conducting the Twickenham Choral Society. 'This still is so important to me, I've been doing it for nearly 30 years. We've just done Monteverdi's 1610 Vespers, and we have Britten's War Requiem and Tippett's Child of our Time planned for next season. Working with singers and orchestra always keeps me in touch with what all organ playing should be about: because the organ is the most dangerous instrument of all: it's the most mechanical. It's the easiest of all to produce sound, and a lot of it. But it's also the most difficult to bring to life, to make it rhythmical and melodic: to make it sing and breathe!'. |

The Wall Street Journal

|

The Wall Street Journal ... Personal Journal ... Time Off / Backstage ... Christopher Herrick [29 October 2004] ONE OF EUROPE'S most acclaimed organists is 62-year-old Christopher Herrick. Formerly of Westminster Abbey, Mr. Herrick now performs all over the world, his playing universally praised for its clarity, brilliance and apparent ease. He has recorded for a number of labels, including Decca, Virgin Classics and Hyperion -- for which has made more than 30 CDs, including the complete works of Bach and the popular 10-CD Organ Fireworks series. These prize-winning discs have been recorded on some of the greatest organs in the whole world. During a stop in Trondheim, Norway, to perform on the historic organ of Nidaros Cathedral (as part of the St. Olav's Festival), the lean, white-haired musician paused to chat with Benjamin Ivry at Mr. Herrick's hotel overlooking the Niv River. Q: As a boy, you sang in the choir of St. Paul's Cathedral, London. What did you learn there? A: I recall when I was 12, the St. Paul's organist, Sir John Dykes Bower, asked me to accompany him to the cathedral organ loft to turn pages for him for a BBC recording. Normally he was a very straightforward player, not flashy; but that day he was flashy, using the full resources of the magnificent St Paul’s Cathedral organ, and I was suddenly sure that’s what I wanted to do. Q: As a young musician did you listen to recordings of organists like E. Power Biggs or Albert Schweitzer? A: I've always been a bit arrogant about organ recordings. There were a few on 78s and most were badly performed. I'm sure Schweitzer had his virtues but I'd never imitate his way of playing. I tell students to listen to lots of people play, but don't be a clone. Q: Are there national schools of organ playing? Do French organists play differently than the British or Germans? A: The organ is becoming more and more internationalized. There tends to be a kind of consensus way of playing. Germans want to play more like Frenchmen or British; they look beyond their boundaries to learn things. We organists have a mutual admiration for different ways of doing things. Q: You've recorded a two-CD set of the music of the Dutch composer Jan Pieterszoon Sweelinck (1562-1621), whom Glenn Gould preferred to Bach. Was Gould right? A: I can't say I prefer him to Bach, but Sweelinck is a sadly neglected master. Sweelinck is a real link between the English Elizabethan composers and Bach, because he taught the great German composers before Bach, like Samuel Scheidt. Sweelinck's music is wonderful because it's so clever and exciting. Q: Yet to record his music, you had to devise a different, quite painful way of moving your fingers on the keyboard. A: I probably already had some tensions (in the hands), which most musicians would admit to -- a form of repetitive stress injury. . . . To play in Sweelinck's old style, not using the thumb very much, I was doing new things with the other fingers; and only when I went in for physical therapy did I finally adapt. Q: In 1998 you played the complete organ works of J.S. Bach, 14 concerts on 14 consecutive days. Did you ever think that Bach himself never had to do this, and it's too much? A: No. Bach is just so totally satisfying, that even his less-than-top works are so exciting. Q: How did you wind up recording all of Bach's organ music? A: Wind up is right. It started by chance. I was asked by Hyperion to record Bach's trio sonatas, and the company's director, Ted Perry, even wrote to me saying, "No complete Bach, Christopher." He didn't want it. The Bach idea crept up on him, as it did on us, and finally he said, "The world needs this, Christopher." Q: Why did you record the cycle on a modern Swiss organ made by Metzler? A: A friend of mine who is a Swiss geologist responsible for burying nuclear waste is also a great organ fan. He went with me to see a new organ in a village church in Switzerland. It struck me that this was the right organ for the Bach trio sonatas, with lots of colors in its sound, but not a big volume. It might almost have been a chamber organ, it was so warm and beautifully balanced. As we went on doing the series we tried out other Metzlers, which were fine instruments. Q: You enjoy playing works you call "high-cholesterol romantic concertos." What do you mean? A: To be honest, I lifted the term from someone else; it's so neat, and gives the idea of something rich, like whipped cream. Q: Although the organ can produce such a huge sound, do you still have to worry about outside traffic noise in recording? A: Yes, we've had plenty of problems like that. At Halmstad someone started mowing the lawn while we were recording -- so you go and ask them to stop. . . . In Bremgarten, we got the police to stop traffic on the street for the first Bach recording. But when we returned for later recordings, they wouldn't do it. Maybe they'd had protests from shopkeepers. As a compromise, drivers were not allowed into the street near the church, but the ones parked nearby were allowed out -- slamming their doors and going into pubs with their friends. Q: You are also a choir conductor, leading the 120-strong Twickenham Choral Society of West London. What's the difference between playing the organ and conducting a choir? A: The organ is potentially the most unmusical of instruments because it's the most mechanical. People who play it unmusically either don't breathe, or are not rhythmically alert. It's no good just being an organist. You must have a wider experience of music -- quite apart from the fact that I'm happy to direct a choir and it gives me a ready-made social life. Q: You were impressed when you saw the Grand Canyon. And organist and composer Olivier Messiaen was also inspired by Bryce Canyon, Utah. Are organists especially susceptible to vast natural wonders -- or just vastness, itself? A: Maybe. My ambition as a child was to drive a great big steamroller, the kind which flattens the road. I was saving up for one through most of my boyhood, but used the money, instead, to help buy a piano. Maybe I wanted to steamroll with the organ. Might be a power complex. Q: The fourth volume of your Organ Fireworks series includes "Passacaglia" by Dmitri Shostakovich. Would you say he was a good organ composer? A: That music originated in Shostakovich's opera "Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk" -- and when I first heard it in the opera house, sweat was pouring off my brow. It was so full of horror, redolent of what Shostakovich went through during the Stalinist era. His version of it for organ isn't very well written for the instrument and it needs to be edited to be playable. But it's such fantastic music. |

Fireworks and Dreams

|

Pipedreams, American Public Media ... Fireworks and Dreams [October 2009] |